All it took was 10 days to devastate the waters of Tampa Bay for months. The nearly “catastrophic failure” of Piney Point, a former phosphate mining facility, unleashed millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into local waterways, and new research, published on the anniversary the leak at the facility began, reveals just how devastating it was.

The incident began last year when the company in charge of Piney Point, HRK Holdings, found a tear in the liner of a gypsum stack. That liner is what essentially prevents millions of gallons of mining wastewater and dredged materials from seeping through a phosphogypsum stack – a massive mound made up of phosphorus mining byproduct. That leak started to impact the structural integrity of the entire stack, prompting officials to evacuate residents over concern that the stack would totally collapse and unleash a massive wave of water.

To prevent that from happening, officials had to pump that wastewater into local waterways. Over the course of 10 days, more than 215 million gallons of wastewater filled with environmentally toxic levels of nutrients were unleashed into Tampa Bay.

Marcus Beck, lead author of the new environmental impact study, told CBS News it was “the largest release that [the facility has] had to date.” The water contained high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen, nutrients that when dumped into the bay at the levels they were, can create “a cascading environmental response that is not good for other resources in the bay.”

Marcus Beck/Tampa Bay Estuary Program

“It’s something that the ecology, the system, can’t handle,” Beck said. “…Tampa Bay is an estuary that is nitrogen-limited, meaning that if you put nitrogen in the system it’s going to fuel algae blooms. And there’s all sorts of cascading effects that can happen from that as a result.”

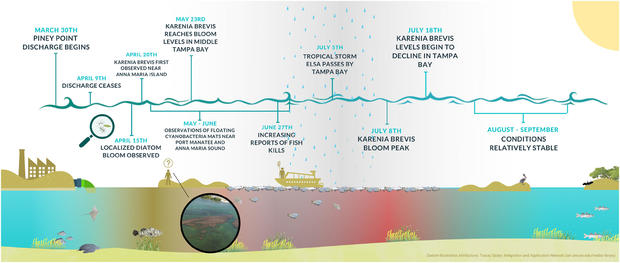

A year’s worth of nitrogen – 180 metric tons – was discharged into the bay from March 30 to April 9. By April 15, Beck and his team started to observe a “run of the mill, non-harmful species” of algae that had bloomed around the Piney Point discharge site. In May and June, abnormal “large floating mats” of filamentous cyanobacteria had appeared just south of Tampa Bay, which Beck said can be harmful at large volumes.

Those mats soon went away, but that’s when red tide, a massive algae bloom that’s hazardous to both marine and human life, started to peak. Red tide originates in the Gulf of Mexico and shows up in Tampa Bay when conditions are conducive to its growth. In the past, it happened when rain was minimal and ocean salinity was high.

But 2021 saw the highest concentrations of red tide in the area since 1971, according to Beck, creating heavy fish kills and pushing people from the beach as the neurotoxins from the algae caused eyes and noses to burn.

“Red tide is toxic,” Beck said.

Between the bloom at the discharge site, the giant mat of cyanobacteria and the aggressive bout of red tide, Beck said it was a clear indication that “this was not a normal year for the bay.” Although the discharge of wastewater at Piney Point didn’t cause the red tide, the researchers said there are “multiple lines of evidence for an adverse environmental response.”

“What we think happened is that when perhaps the red tide migrated into the bay from the Gulf, there was essentially a lot of food available for it — nutrients that were either there from the original discharge or they were released after decomposition of the initial phytoplankton bloom or the cyanobacteria,” Beck said.

Marine Pollution Bulletin

And now, a year later, there is still a risk it could all happen again. As of April 15, there is approximately 258 million gallons of wastewater still in the gypsum stack.

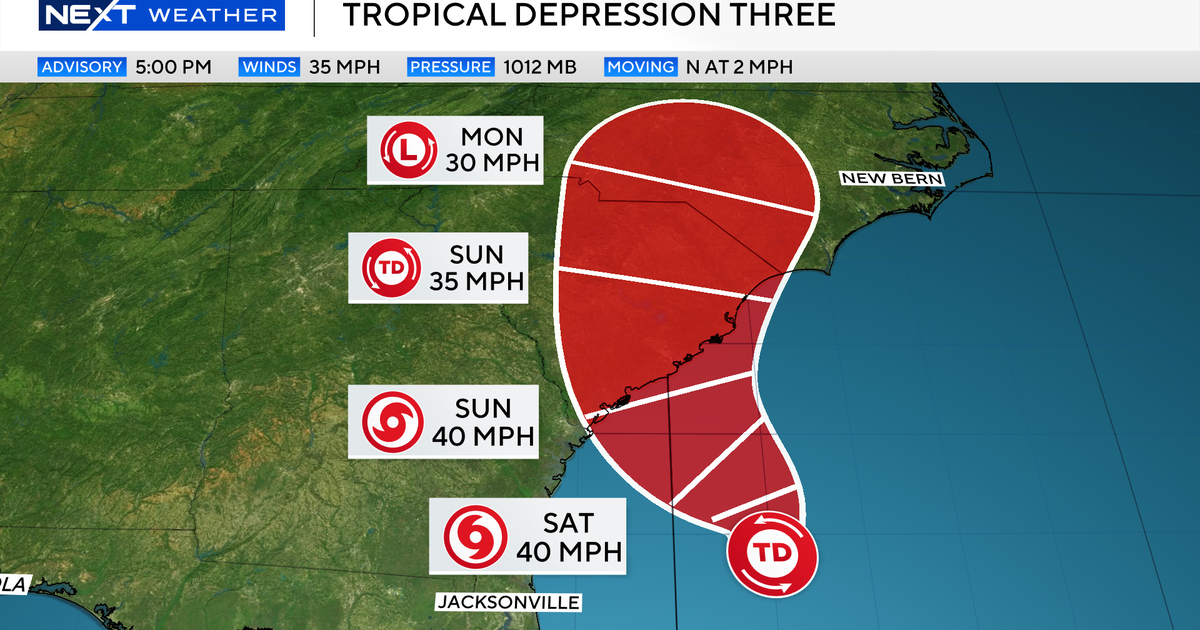

The state approved a plan to close the stacks, a deep injection well, a year after the spill, but it could take another year before it’s ready to be filled with the water. Meanwhile, Florida’s rainy season is only months away and will be closely followed by hurricane season, which The Weather Channel has predicted will be busy.

“A scary thought”

Manatee County Commissioner Scott Hopes told CBS News that the gypstacks have capacity for about 25 inches of rain.

“That’s a scary thought because it just takes an above-normal storm season during our hurricane season to potentially drop more water than the stacks can hold,” Hopes said. “Fortunately, there are some other sort-of backup retention ponds.”

The water still being stored is undergoing treatment. Hopes said between 100 and 150,000 gallons a day go through the treatment plant, and Beck said the nitrogen load has been reduced from about 200 milligrams per liter down to three or four milligrams per liter. But those levels are still above the baseline nutrient concentrations in Tampa Bay, so if another spill is to occur, it would be a “significant load influx.”

“That would still be a concern, however, not nearly a concern of what it was last year when they had the initial release,” Beck said. “Stormwater management is always going to be a concern at that place until the water is 100% removed.”

Even with the closure at Piney Point, there are more than two dozen other phosphate mining facilities in Florida – nine of which are still active, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Chad Smith/Tampa Bay Water Keeper

“When you have an industrial site that has this type of material and structure, there’s no doubt in anyone’s mind that this has a potential hazardous risk for the environment,” Hopes said, adding that issues at Piney Point should have been resolved years ago.

“There was an opportunity to write the final chapter before HRK took this site over and that’s what should have been done,” he said. “…Only companies that have experience with managing this type of industrial site should be involved with this type of industrial site.”

Hopes said he thinks “many people have learned a lesson” and that he “would not expect” what happened at Piney Point “to ever occur again in the state of Florida.”

But several other sites have had their own hazardous problems. In 2016, a 45-foot-wide sinkhole opened up underneath a gypstack at a phosphate fertilizer plant in Mulberry, Florida, unleashing at least 215 million gallons of wastewater into the Floridan Aquifer, according to The Tampa Bay Times. And a few weeks ago, the state announced it’s investigating a possible tear in the lining of a gypstack in Polk County, according to WUSF Public Media. Mosaic, the company that owns both of those sites, is seeking a permit with Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection to expand a gypstack at the facility thought to have a tear in the liner.

“I understand the value of fertilizer in modern society…but I think what needs to be done is just greater oversight and perhaps more regulatory oversight of just what is the long-term implication, the long-term management of these sites moving forward,” Beck said. “…If there’s a new location, making sure that there’s a plan, that wastewater or any other environmental impacts from that site, are taken care of in a manner that is not externalized to the community or the local environment.”

Beck and his team are now studying the longer-term implications of last year’s discharge, particularly looking at the impact it may have had on seagrasses, which can take a little longer to respond to environmental changes. Seagrass is a critical part of the bay ecosystem and a vital food source for manatees, which died in record numbers last year, mostly from starvation.

“We can just hope for the best, having these types of conversations and making people aware that these are concerns,” Beck said, “…and making sure that folks that need to be held accountable for managing these sites in a responsible manner are actually held accountable.”