Less than 36 hours before they were killed last month, Rob and Michele Reiner sat in a Los Angeles theater watching “Lyrics from Lockdown,” a one-man show about race, justice and mass incarceration in America.

The show focuses on Nanon Williams, who is serving his 34th year in a Texas prison for a murder he says he didn’t commit — and who, over the past decade, quietly forged a remarkable relationship with the Reiners.

Rob, a famed director, and Michele, a photographer, producer and activist, had come to love Williams, 51, like a son, emailing him almost daily. They had invited him to live with them if he ever got out of prison. Their daughter, Romy, called Williams her big brother.

“He became like family,” Romy said in a statement to NBC News.

For more on this story, watch “Hallie Jackson NOW” on NBC News NOW on Tuesday at 5 p.m. ET

The Reiners’ bond with Williams, which has not previously been reported, was built on ideals that animated much of Rob’s work — love, chosen family, compassion and redemption. After being charged with murder at 17, Williams had spent his entire adult life behind bars, much of it in near-total isolation. The Reiners lived in a world defined by film premieres, public platforms and near-constant access to power. The connection they discovered was as profound as it was unlikely.

The Reiners were “an integral part of my life,” Williams told NBC News in an interview from prison last week. “They became a part of me.”

On the last Friday evening of the Reiners’ lives, Dec. 12, words that Williams wrote from prison about survival were read from a Los Angeles stage. Williams’ mother and sisters were in the audience, along with the woman he’d fallen in love with and married from prison. The Reiners were on a double date with their dear friends, Billy Crystal and his wife. Romy came, too.

The mood was electric. Williams’ fight for freedom had been gaining traction. His case was back in court, fueled by evidence discrediting the ballistics testimony that helped convict him for a 1992 shooting.

In the theater that night, Rob spotted Williams’ sister, Angela Grant Clayton, and hugged her.

“We’re going to make sure Nanon gets out,” he told her.

Williams’ mother, Lee Diana Bolton, said Rob and Michele pulled her into a tight, lingering embrace.

“These were not phony people,” she said later. “These were the sweetest, most loving people that I have ever met.”

After the show, the Reiners gathered with a small circle of advocates who had been pressing for Williams’ exoneration. Georgetown professor Marc Howard was one of them. Near the stage, they all discussed the latest developments in Williams’ appeal.

“It was a conversation so full of hope, happiness,” Howard said later. “It felt like the very next step was Nanon coming home.”

Two days later, on Dec. 14, Nanon Williams was at the W.F. Ramsey Unit, a maximum-security prison about 40 miles south of Houston, speaking with other incarcerated men about health, trauma and survival.

When he returned to his cell, he opened his state-issued tablet — his main window to the outside world — and saw a news alert. Two people had been found dead in a home owned by Rob and Michele Reiner.

Williams immediately typed a message to Michele. “Please, this can’t be true,” he wrote. “Please tell me the news is lying.”

Soon, though, his fears were confirmed: The Reiners were dead, and their son, Nick, had been charged with murder. Two of the people Williams was closest to in the world were gone, and he was left to grieve alone.

Receiving emails in prison can take hours, sometimes days. Messages are screened and scrutinized, creating delays that become agonizing in times of crisis.

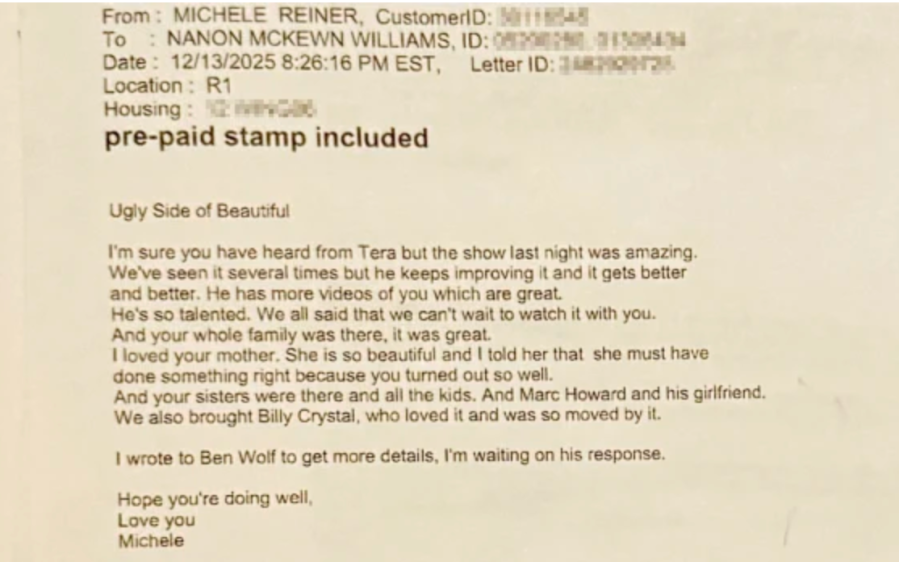

In the days that followed, three new emails from Rob and Michele appeared on Williams’ tablet. Michele’s final message was timestamped Saturday, Dec. 13 at 8:26 p.m. EST. She’d sent it the day after seeing “Lyrics from Lockdown” — only hours before her death.

The subject line read: “Ugly Side of Beautiful”

“I’m sure you have heard from Tera,” Michele had written, referring to Williams’ wife, “but the show last night was amazing.”

She wrote about meeting his mother. How beautiful she was. How Billy Crystal was moved by the performance. And about hope for Nanon’s future.

“We all said that we can’t wait to watch it with you.”

She signed off the way she always did.

Love you

Michele

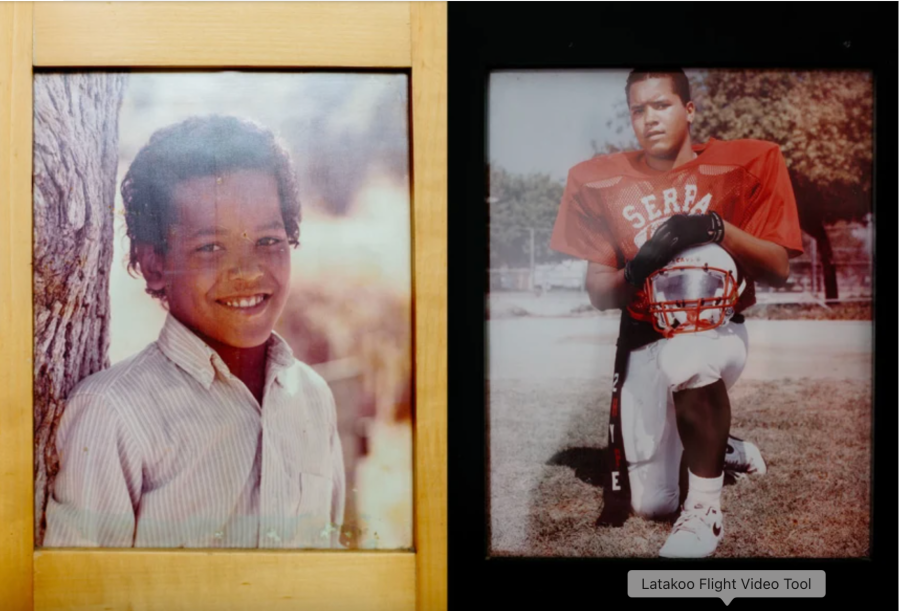

Nanon Williams grew up in Los Angeles amid violence and chaos. As a toddler in the 1970s, he visited his father in prison. His mother had also been in jail on drug charges. At 7, Williams witnessed his uncle gunned down in the doorway of his home.

By the time he turned 11, his dad had come home, but their life together didn’t last long. He was shot and killed over drug territory. Williams went to live with relatives. Today, his mother is a steady presence in his life.

As a teenager, he was on his own, buying and selling drugs.

That’s what he was doing on the night of May 13, 1992, while visiting his grandparents in Houston. Several people met at a city park. Williams and others carried guns. Something went wrong. Multiple shots were fired. A 19-year-old named Adonius Collier was killed.

Williams was 17, too young to vote or buy alcohol, but old enough to face the death penalty.

The state’s case rested on two pillars: the testimony of a co-defendant, Vaal Guevara, who said he watched Williams pull the trigger, and a ballistics expert who said the bullet recovered from Collier’s skull came from Williams’ .25-caliber handgun — not from Guevara’s .22 Derringer.

Guevara, who admitted he’d also shot at Collier but claimed he missed, had taken a deal: plead guilty to a drug charge, testify against Williams and serve 10 years. He ultimately served only four.

Williams acknowledges he fired his gun in the melee; witnesses said his shots injured another man. But he denies shooting Collier.

“I’ve done wrong,” Williams said. “But killed someone? No, I’ve never killed anyone.”

At his 1995 trial, prosecutors described the ballistics evidence tying Williams to the murder as “uncontradicted” and “failsafe.” His lawyer never challenged it.

The jury convicted Williams and sentenced him to death.

He remembers the judge telling him, “the sentence is until you’re dead, dead, dead.” He heard his mother cry out. His grandmother collapsed.

He was shipped off to death row, where he lived in solitary confinement in a small, dark cell near other men waiting for their scheduled dates to die. He began measuring time by executions. One by one, men he’d come to know were taken away and never returned.

“I used to feel guilty about living,” Williams said. “I used to wonder why I was still here.”

He began etching their state-assigned numbers into his skin with a needle and ink — his own private ledger to remember them. Up his arms. Across his chest. Down his legs.

“Now I know 466 men who were executed,” he said.

Three years after his conviction, much of the evidence used against Williams began to fall apart.

In 1998, his appellate lawyer requested testing of Guevara’s .22 Derringer. Prosecutors asked the same ballistics expert who testified at trial to test-fire the gun — something he’d never done.

The analyst, Robert Baldwin, wrote a 1998 letter to the prosecutor with his results. He said he’d been wrong. The bullet taken from Collier’s head had, in fact, been fired from Guevara’s .22 Derringer, not Williams’ gun.

In 1999, the prosecutor wrote a letter opposing Guevara’s parole. In it, he made a stunning admission about his star witness: “At trial Guevara was very evasive and apparently not at all truthful,” he wrote. The additional evidence, the prosecutor said, indicates that Guevara, “rather than merely being a witness, likely participated in Collier’s murder.” Guevara didn’t respond to messages from NBC News.

A juror from Williams’ trial later signed an affidavit filed in Williams’ case saying the new evidence could have changed her verdict; another said definitively she would have voted to acquit.

In 2001, a state judge held post-conviction hearings and concluded Williams deserved a new trial. But the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected her recommendation.

Williams remained in prison, awaiting his turn to die.

The story of how a legendary Hollywood director and his wife became like family to a man convicted of murder began with letters and a poem.

In 2003, from death row, Williams learned about a “60 Minutes” segment on a Harvard Law School student who was swept into the criminal justice system simply for being Black.

Bryonn Bain had been walking past a crime scene in New York with his brother and cousin when all three were arrested; they were ultimately cleared.

Inspired, Williams wrote Bain letters about his own plight. Then he sent a poem called “Parallel Universe.”

What if Bain had grown up in Los Angeles as Williams had, instead of on the East Coast? What if Williams had Bain’s parents and opportunities? In a parallel universe, Williams wrote, maybe he’d be the one at Harvard. Maybe Bain would be the one facing execution.

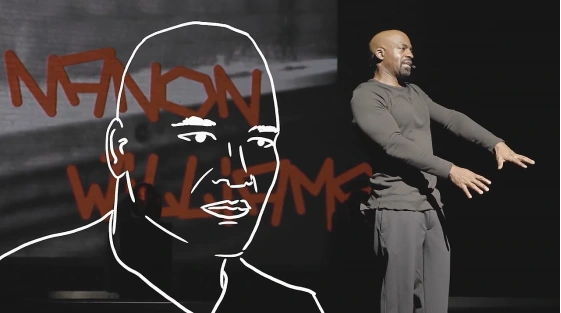

Bain, who also wrote poetry, began conceiving a stage show where he would weave his lived experience and Williams’ writings into a spoken-word, multimedia performance.

The result was “Lyrics from Lockdown,” which premiered at the National Black Theatre in 2013, with singer and activist Harry Belafonte and his daughter Gina executive producing.

By then, Williams was no longer on death row. After the U.S. Supreme Court banned executions in 2005 for crimes committed by juveniles, his sentence had been reduced to life without parole.

In 2016, Rob and Michele Reiner saw “Lyrics from Lockdown” in Los Angeles. They were struck by Bain’s performance and asked him to introduce them to Williams. They sent a letter, then arranged a phone call.

Williams had gone decades with little access to movies or television. “I didn’t really know who Rob was,” he recalled.

He came to know Rob and Michele as kind voices on the phone. They asked questions, offered advice and showed genuine interest in getting to know him. Only gradually did it sink in that Rob was the filmmaker behind some of Hollywood’s most beloved movies, including “A Few Good Men” and “When Harry Met Sally…”

None of that mattered to Williams. What mattered, he said, was that they were listening.

“The more they learned,” Williams said, “the more pissed off Rob became, and the more loving Michele became.”

The Reiners’ initial interest in helping him wasn’t surprising. Rob had spent decades opposing the death penalty; Michele, whose mother survived Auschwitz, carried a lifelong sensitivity to dehumanization and state violence.

But what followed would go far beyond advocacy.

Rob signed on as an executive producer of “Lyrics from Lockdown.” The show traveled across the country, into prisons and revered public spaces: Carnegie Hall. The Apollo Theater. Lincoln Center.

Each performance carried Williams’ story further — and drew more people in.

In October 2018, Georgetown professor Marc Howard, founder of the university’s Prisons and Justice Initiative, saw the show at the Kennedy Center.

“What was screaming out at me was, this man has something special,” Howard said of Williams. “The letters that he’s written, they hit home. They give me the chills.”

Soon, Howard joined a tight circle of supporters who held regular Zoom calls about Williams’ case. He found himself on screens with Rob and Michele Reiner.

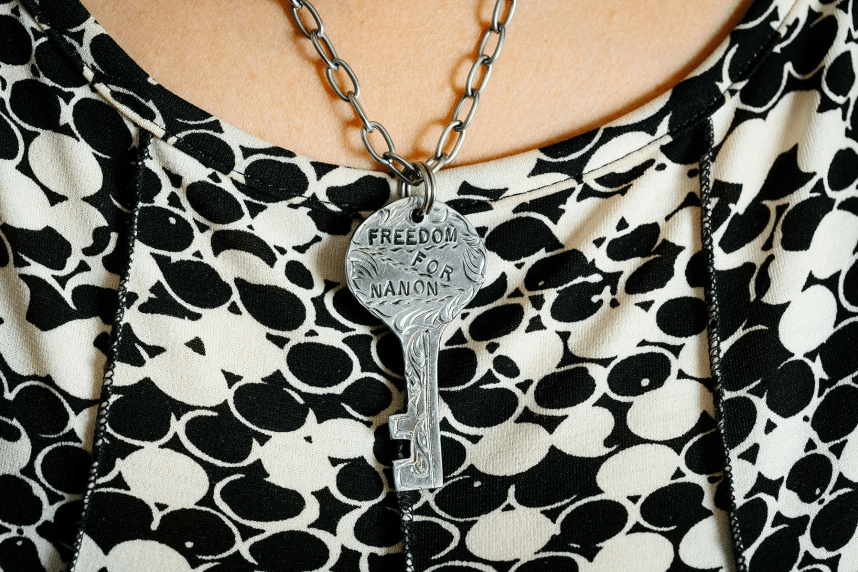

What began with poetry had become a movement for freedom.

Williams’ budding relationship with the Reiners was constrained by the barriers of prison life. Calls had to be scheduled. Letters could take weeks.

In 2021, a decision by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice narrowed that distance. It issued tablets to tens of thousands of incarcerated people.

Suddenly, he and the Reiners could email whenever they wanted. What was at first a cordial relationship quickly grew into something much deeper.

Williams described Rob as warm and curious, someone who asked questions that helped him make sense of his struggles. With his tablet, Williams could finally see some of Rob’s movies.

Michele wrote most often, asking Williams how he was sleeping, whether he was eating, how he was holding up emotionally. She told him about her family, her childhood, her mother’s survival of the Holocaust. Over time, Williams came to think of her as a mother figure who offered reassurance without judgment, who listened as much as she spoke.

“Michele was my heart,” Williams said.

The Reiners folded Williams into their lives. They introduced him, virtually, to their children, Jake, Nick and Romy. They treated him less like a cause and more like kin.

“Rob and Michele didn’t want credit for trying to help me,” Williams said. “It was just because they loved me.”

It’s not just Williams saying that; it’s the Reiners’ children, too. “My parents spoke about him with such love,” Romy wrote in a statement to NBC News this week. “He has taught me more about life and human compassion than anyone I’ve ever met.”

Jake said in a statement that his parents “were fierce in doing everything in their power” to help Williams get out one day. “I know wherever they are,” he wrote, “they are beaming with pride for him.”

The kind of pride only a parent could understand.

A few years ago, Williams met a woman who’d heard about his case. They fell in love. But Williams wrestled with what should come next. Was it fair for him to marry someone while living in bondage?

“I had a fear of my chains becoming hers,” Williams said.

He shared his concerns with Rob, who responded by asking Williams what he remembered after recently watching his classic fairytale comedy, “The Princess Bride.”

“I learned it was about true love,” Williams recalled telling him.

Rob replied, “Your story is about true love. If you don’t fight for love, Nanon, what would you fight for?”

Encouraged by Rob, Williams decided to get married.

By then, Howard, the Georgetown professor, had traveled to Texas nearly a dozen times to visit and had also become like family. Williams knew that Howard had officiated weddings for friends, so he asked Howard to marry him and his wife, Tera.

“It was the most amazing moment I’ve ever had in my life,” Williams said.

A year later, it seemed as if even better days might be possible.

In 2024, after a complaint filed by the University of Colorado Law School’s Criminal Defense Clinic, the Texas Forensic Science Commission issued a 157-page report officially confirming that the ballistics testimony used to convict Williams was wrong. The Innocence Project joined the effort soon after.

Last year, Williams’ legal team requested a new trial under a Texas law enabling people to challenge convictions based on “junk science.” The Harris County District Attorney’s Office opposed the request, saying in a statement that it was “confident the conviction is warranted.”

Rob, Michele and Romy all wrote letters on Williams’ behalf.

“He is the most intuitive person I’ve ever known,” Michele wrote of Williams. “And although he says we have given him so much, he has given me so much more.”

Rob’s letter took Williams’ breath away.

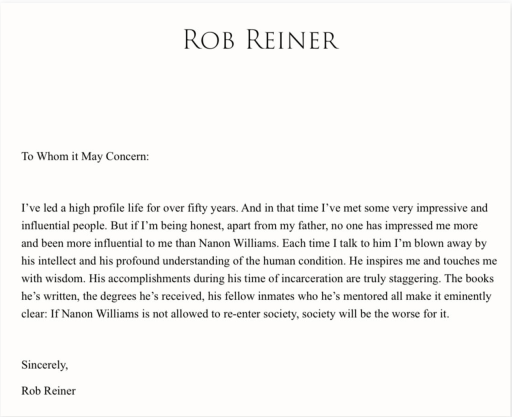

“I’ve led a high profile life for over fifty years,” Rob wrote. “And in that time I’ve met some very impressive and influential people. But if I’m being honest, apart from my father, no one has impressed me more and been more influential to me than Nanon Williams.”

Apart from my father.

He was talking about Carl Reiner, the comedian, writer and director.

“It’s overwhelming,” Williams said. “I don’t even know how to digest that.”

More recently, Williams had been working on ideas to spread Rob’s wisdom to the men around him. The plan was for Rob to visit the prison and screen his movie, “Stand By Me,” then lead a discussion afterward.

Williams asked his sister to order rubber bracelets emblazoned with the movie’s title. They were distributed throughout the prison. Men who had never heard of Rob Reiner began talking about what the title meant. What it means to stand by someone.

The screening was scheduled for December.

It never happened.

Last week, Williams sat in the visiting room at the W.F. Ramsey Unit, emotional and exhausted.

“I have not hardly been asleep,” he said.

He’s thought constantly about Rob and Michele. About the emails that arrived too late. About the “Stand By Me” screening that’ll never happen. About Nick Reiner.

When news broke that Nick had been arrested and charged with two counts of first-degree murder, Williams sat with the weight of it — and the irony.

“I was judged to be a killer, a monster beyond redemption,” he said slowly. “The question I ask myself is, ‘What would they want for their son?’”

He let the question hang in the air.

“What love and compassion and understanding would they want for him? If they would have it for me, why not him?”

He recalled the Reiners’ love for their son as they tried to support him through his troubles; authorities have said Nick was diagnosed with schizophrenia and sources familiar with his behavior say he had been acting erratically before the murders. He hasn’t entered a plea.

The parallels are staggering. A judge could soon issue an order on whether Williams’ appeal can move forward, the same month Nick is expected to face arraignment. News reports suggested Nick could face the death penalty, the same sentence Williams once received.

“I understand being caged like an animal,” Williams said. “I understand the pain that is to come. The reflection. Looking into the mirror, wondering if you harmed your own soul by the choices you’ve made.”

Wearing a “Stand By Me” bracelet, he looked down at his hands — scarred knuckles, tattooed arms covered in numbers, each one representing a man who had been killed by the state.

“I have a responsibility to Nick,” he said finally. “If I ever get out of here, how could I not try to do something to help him?”

Williams has spent 34 years thinking about culpability and compassion. Judgment and grace. What it means to be deemed irredeemable.

He learned to forgive people who killed his father, who took his mother away, who sent him to death row for a crime he says he didn’t commit.

But it was his relationship with the Reiners that finally healed his anger.

“I feel like Michele stole it from me,” he said softly.

The Reiners left him with something, too — a lesson Rob repeated again and again.

“The greatest stories,” he had told Williams, “should be about love.”

Even when they break your heart.

Rob and Michele Reiner’s daughter and older son are speaking out on the couple’s shocking deaths. Jake and Romy Reiner broke their silence on the tragedy in a statement on Dec. 17, three days after their parents died at their Los Angeles home in an apparent homicide.